Forest Pest & Disease Alerts

|

There are numerous invasive pests and diseases that landowners should be aware of for a variety of reasons: how to treat and prevent spreading infections, how to identify pests not yet found in Michigan (and who to contact if they believe they found something of concern), and where to participate in community science initiatives aimed at cataloguing pests' spread across the United States and notifying professionals where remnant trees of species of concern exist. A lot of this content is owed to the hard work of our 2023 Summer Forestry Intern for the LCD, Sam Bull (Northland College - Class of 2024).

For any questions or wanting to learn, please contact Ellie Johnson ([email protected], 231-866-0103). If you believe you may have any of the pests listed here present in your forest, you can send Ellie a picture or contact:

|

Oak Wilt

Leaves will often appear brown, tan, copper, or brassy and will drop off an infected tree. Photo: MSU ext.

Leaves will often appear brown, tan, copper, or brassy and will drop off an infected tree. Photo: MSU ext.

Ecology

Bretziella fagacearum, an exotic fungal pathogen of unknown origins, has been known to decimate oak trees (Quercus spp.) and this process is visibly seen as “oak wilt”. It is 100% fatal to members of the red oak group, which includes species like northern red oak (Quercus rubra), northern pin oak (Q. palustris), black oak (Q. velutina), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea). The fungus impacts the tree’s cambium layers, blocking water flow in a tree’s xylem wood (similar to a person’s circulatory system) and leading to tree mortality in a matter of weeks. Like other fungi, B. fagacearum is spread by spores, and they are carried by nitulid beetles, or picnic beetles, that are attracted to sweet substances like tree sap. When an oak is injured, the exposed sap layers attract hungry insects, and if they’re carrying the spores the tree can become infected. There is no cure for a tree infected with oak wilt.

Once the fungus is inside a red oak tree, symptoms may show themselves within 4 weeks. From that initial infection it can spread to neighboring oaks via underground root grafts. The rate of spread depends on the soil type and the size of the trees. Spores are grown by the fungus on mycelial mats underneath the bark, pushing it apart and causing it to crack. The exposed mats have a sweet smell (similar to Juicy Fruit gum) which in turn attract insects that can start the cycle all over again on a different injured tree.

Bretziella fagacearum, an exotic fungal pathogen of unknown origins, has been known to decimate oak trees (Quercus spp.) and this process is visibly seen as “oak wilt”. It is 100% fatal to members of the red oak group, which includes species like northern red oak (Quercus rubra), northern pin oak (Q. palustris), black oak (Q. velutina), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea). The fungus impacts the tree’s cambium layers, blocking water flow in a tree’s xylem wood (similar to a person’s circulatory system) and leading to tree mortality in a matter of weeks. Like other fungi, B. fagacearum is spread by spores, and they are carried by nitulid beetles, or picnic beetles, that are attracted to sweet substances like tree sap. When an oak is injured, the exposed sap layers attract hungry insects, and if they’re carrying the spores the tree can become infected. There is no cure for a tree infected with oak wilt.

Once the fungus is inside a red oak tree, symptoms may show themselves within 4 weeks. From that initial infection it can spread to neighboring oaks via underground root grafts. The rate of spread depends on the soil type and the size of the trees. Spores are grown by the fungus on mycelial mats underneath the bark, pushing it apart and causing it to crack. The exposed mats have a sweet smell (similar to Juicy Fruit gum) which in turn attract insects that can start the cycle all over again on a different injured tree.

Treatment

To treat oak wilt, MSU extension has outlined the following management strategies. Oak wilt is dynamic and can be costly to treat so a professional consult is the most efficient and cost-effective way forward.

To treat oak wilt, MSU extension has outlined the following management strategies. Oak wilt is dynamic and can be costly to treat so a professional consult is the most efficient and cost-effective way forward.

- Do not prune oak trees during the high-risk period from April 15 to July 15. This will help prevent overland spread. If possible, limit other activities that could cause wounds during the warm months of the year.

- If wounds do occur during the summer (e.g., from storms), paint the wounds with tree wound paint or latex-based paint as soon as possible. Beetles have been known to find their way onto wounds within ten minutes of pruning.

- Do not move firewood from trees killed by oak wilt. If you cut a dead oak for firewood, stack the wood then cover the pile with a plastic sheet (minimum 4 millimeter thickness) and bury the edges of the plastic underground. Leave the plastic over the woodpile for six to 12 months until the wood is dry and the bark sloughs off. At that point, the fungus can no longer survive in the wood.

- Report suspect trees to the Department of Natural Resources Forest Health Division by emailing [email protected], calling 517-284-5895 or through their online reporting tool by selecting the “View and Report Oak Wilt Locations” bar.

- Get a lab verification of oak wilt via MSU Plant & Pest Diagnostics. Unless a mycelial mat is observed on a dead tree, the presence of oak wilt must be verified by plant pathologists before any management actions begin. See MSU Plant & Pest Diagnostics’ specific sampling instructions.

- Consult with Ellie for a diagnosis and a certified arborist for treatment and mitigation.

Works Cited and Extra Resources

- How to collect and submit samples to MSU plant diagnostic lab, MSU extension: https://www.canr.msu.edu/pestid/submit-samples/wilted-trees-and-shrubs

- How to identify, prevent, and control oak wilt, US Forest Service: https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/lands_forests_pdf/oakwiltusda.pdf

- Oak wilt coalition: https://www.michiganoakwilt.org/

- Oak Wilt Treatment, MSU extension Oak wilt treatment - MSU Extension

- Oak wilt viewfinder (see current outbreaks and submit possible new spots), Michigan DNR: https://midnr.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=aa4075c218ad4b968f15f14f84b37387

- Smart Gardening to Prevent Oak Wilt, MSU Extension: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/smart-gardening-to-prevent-oak-wilt

- Worried About Oak Wilt, MSU Extension https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/worried_about_oak_wilt

Beech Bark Disease

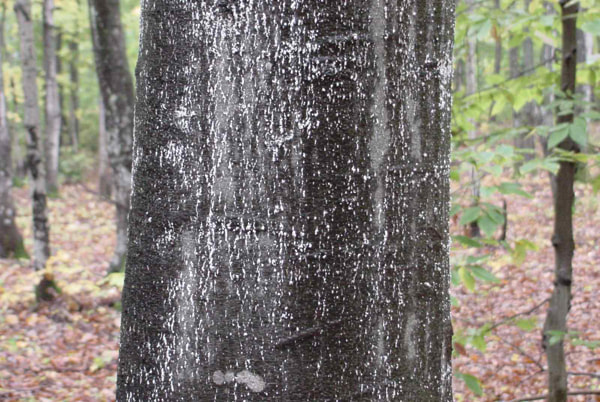

Beech scale will usually first be seen wherever the bark has more character, such as branch scars. Photo: Ellie Johnson

Beech scale will usually first be seen wherever the bark has more character, such as branch scars. Photo: Ellie Johnson

Ecology

Beech bark disease (BBD) is caused by multiple levels of infestation from the sap sucking crawler insects called beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga Lindinger) followed by two types of Nectria fungi and possible other pathogens. Its presence will eventually lead to the death of the infected American beech tree (Fagus grandifolia), though there are research studies that suggest some beech (5%) may be resistant (Koch, Mason and Carey, 2015). Beech scale are tiny insects with straw-like mouthparts (stylets) which they poke through the bark and feed on the sap layer immediately underneath. The numerous, tiny holes left by the insects can expose the tree to further infection by the Nectria fungus and possibly other diseases, which destroys internal woody tissues. Ladybird beetles (Chilocorus stigma) often feed on beech scale but can’t stop a full invasion. If unchecked, enough woody tissue destruction will girdle the tree leading to its eventual mortality. Due to the multiple infestations, a beech tree becomes structurally compromised, and “beech snap” caused by high winds can occur. The canopy of beech trees can cause serious injury, death or destruction of property depending on the tree’s location. Fungal spores and beech scales can be broadcast great distances by wind and transported by humans in the form of firewood or anything spores or bugs can hitch a ride on.

Beech bark disease (BBD) is caused by multiple levels of infestation from the sap sucking crawler insects called beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga Lindinger) followed by two types of Nectria fungi and possible other pathogens. Its presence will eventually lead to the death of the infected American beech tree (Fagus grandifolia), though there are research studies that suggest some beech (5%) may be resistant (Koch, Mason and Carey, 2015). Beech scale are tiny insects with straw-like mouthparts (stylets) which they poke through the bark and feed on the sap layer immediately underneath. The numerous, tiny holes left by the insects can expose the tree to further infection by the Nectria fungus and possibly other diseases, which destroys internal woody tissues. Ladybird beetles (Chilocorus stigma) often feed on beech scale but can’t stop a full invasion. If unchecked, enough woody tissue destruction will girdle the tree leading to its eventual mortality. Due to the multiple infestations, a beech tree becomes structurally compromised, and “beech snap” caused by high winds can occur. The canopy of beech trees can cause serious injury, death or destruction of property depending on the tree’s location. Fungal spores and beech scales can be broadcast great distances by wind and transported by humans in the form of firewood or anything spores or bugs can hitch a ride on.

|

Signs and Symptoms

Beech scale is detected by trees being covered in a “cotton like” waxy substance in late fall or winter. “Cankers” on the trunk or branches indicate damage done by beech scale. Be sure to pay close attention to spots were old branches and beneath or around patches of lichens for crawlers. Watch for:

Treatment

Due to the complex nature of beech bark disease, it is best to consult an arborist and/or Ellie for a site visit. |

Works Cited and Extra Resources

- Beech bark disease Integrated Pest Management, MSU extension: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/beech_bark_disease

- Invasive species, beech bark disease, Michigan DNR: https://www.michigan.gov/invasives/id-report/disease/beech-bark-disease

- Is it beech bark disease? MSU Ext https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/is_it_beech_bark_disease

- MSU Ext, https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/files/e2746.pdf

- Screening for resistance; Koch, Mason, and Carey, 2015: https://www.fs.usda.gov/psw/publications/documents/psw_gtr240/psw_gtr240_196.pdf

Emerald Ash Borer

Emerald ash borer. Photo: MSU ext.

Emerald ash borer. Photo: MSU ext.

Ecology

In 2002, the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis, also called EAB) was found outside of metro Detroit. Since then, Michigan has lost millions of ash trees, especially black (Fraxis nigra), green (F. pennsylvanica), and white (F. americana). EAB consumes ash trees at every life stage, but it is particularly harmful as larvae. A female will lay eggs on the underside of branches near the trunk, and when those eggs hatch they burrow into the bark and feed on the tree’s cambium layers. They take a couple years to develop, and during that time they are creating tunnels, or galleries, throughout the vascular tissue. This ultimately girdles the tree and kills it. They will then emerge from the trees as temperatures rise in early summer, and adults will feed on the foliage. The exit holes are characteristically D-shaped, as the adult insects have large heads.

In 2002, the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis, also called EAB) was found outside of metro Detroit. Since then, Michigan has lost millions of ash trees, especially black (Fraxis nigra), green (F. pennsylvanica), and white (F. americana). EAB consumes ash trees at every life stage, but it is particularly harmful as larvae. A female will lay eggs on the underside of branches near the trunk, and when those eggs hatch they burrow into the bark and feed on the tree’s cambium layers. They take a couple years to develop, and during that time they are creating tunnels, or galleries, throughout the vascular tissue. This ultimately girdles the tree and kills it. They will then emerge from the trees as temperatures rise in early summer, and adults will feed on the foliage. The exit holes are characteristically D-shaped, as the adult insects have large heads.

|

Works Cited

|

Signs and Symptoms

An infested ash tree will show numerous signs:

Treatment

For treatment the emerald ash borer has a natural predator. Woodpeckers of various species have been observed eating emerald ash borer larvae but cannot stop an entire invasion. Various soil drenching and injection treatments are available and must be used early on in the infestation in order to stop the invasion. If you believe one of your ash trees has an emerald ash borer infestation. Contact a certified arborist and/or Ellie to discuss management options. There are folks who are researching EAB resistant trees, and they want to know where they may exist in Michigan. If you know of any mature (greater than 8in DBH) ash trees that would have endured the EAB outbreak since the beginning, please log them onto the app TreeSnap (https://treesnap.org/). TreeSnap is a community science initiative to find remnant trees for species of concern, like ash trees. Ash trees in Michigan that have withstood the EAB infestation for the last 20+ years have genetics that scientists want to know more about. For more information, visit https://treesnap.org/ or contact Rachel Kappler of Holden Arboretum (https://holdenfg.org/staff/rachel-kappler/). |

Hemlock Wooly Adelgid

Ecology

Hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae annad, also called HWA) has decimated eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) across the eastern United States. Hemlock wooly adelgid was found in Michigan in 2015 and is currently present in the following counties: Allegan, Benzie, Ottawa, Muskegon, Oceana and Mason. In its native habitat in Asia, HWA had natural predators and diseases that kept its population numbers in check, and which are not found in the United States. Mature adults suck critical nutrients out of hemlock leaves and the xylem wood of branches, often causing the trees to go into a stress mode by reducing water flow and leading to significant needle loss followed by eventually mortality (within 4-10 years).

The life cycle of the HWA is complex, but a basic understanding will help determine what treatments may work best for protecting your trees. Two populations of HWA are born on hemlocks each year. The first stage of the insects, called the “crawler” stage, are incredibly small, mobile, and can be moved long distances by wind, migratory birds, or traveling humans. Once they find a host tree, they feed at the base of needles and form white sacs to lay eggs into. The easy way to recognize the adelgid is to look for these sacs under the branches from late fall to early summer. The eggs hatch from the sacs in spring and the “crawlers” will move about until they find a spot to feed. Many may stay on the tree they hatch onto, but again this is the stage that can be moved around. They begin to feed by attaching to the needle base and sucking out critical energy that the tree has stored. Eventually they will produce eggs that will hatch mid summer as the second generation and these “crawlers” will remain active until the fall. They will begin feeding again during the time that conifers are usually storing winter energy. Sacs are produced again that will overwinter eggs and the cycle repeats the following year.

It is important to note all the HWA in the United States is female, and reproduce parthenogenetically (asexually). This means there only needs to be one “crawler” moved to a new location to start an infestation.

Hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae annad, also called HWA) has decimated eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) across the eastern United States. Hemlock wooly adelgid was found in Michigan in 2015 and is currently present in the following counties: Allegan, Benzie, Ottawa, Muskegon, Oceana and Mason. In its native habitat in Asia, HWA had natural predators and diseases that kept its population numbers in check, and which are not found in the United States. Mature adults suck critical nutrients out of hemlock leaves and the xylem wood of branches, often causing the trees to go into a stress mode by reducing water flow and leading to significant needle loss followed by eventually mortality (within 4-10 years).

The life cycle of the HWA is complex, but a basic understanding will help determine what treatments may work best for protecting your trees. Two populations of HWA are born on hemlocks each year. The first stage of the insects, called the “crawler” stage, are incredibly small, mobile, and can be moved long distances by wind, migratory birds, or traveling humans. Once they find a host tree, they feed at the base of needles and form white sacs to lay eggs into. The easy way to recognize the adelgid is to look for these sacs under the branches from late fall to early summer. The eggs hatch from the sacs in spring and the “crawlers” will move about until they find a spot to feed. Many may stay on the tree they hatch onto, but again this is the stage that can be moved around. They begin to feed by attaching to the needle base and sucking out critical energy that the tree has stored. Eventually they will produce eggs that will hatch mid summer as the second generation and these “crawlers” will remain active until the fall. They will begin feeding again during the time that conifers are usually storing winter energy. Sacs are produced again that will overwinter eggs and the cycle repeats the following year.

It is important to note all the HWA in the United States is female, and reproduce parthenogenetically (asexually). This means there only needs to be one “crawler” moved to a new location to start an infestation.

Signs and Symptoms

Similar to beech scale, HWA covers itself in waxy coating. The easy way to recognize the adelgid is to look for these white sacs under the branchlets from late fall to early summer. (left). There are numerous native pests that can be mistaken for HWA. Elongated hemlock scale (Fiorinia externa Ferris) is another hemlock pest that feeds on the needles, but it is a native one and so doesn’t create as dire of circumstances as HWA (center). Hemlock needleminer larva (LATIN) have a pale, yellowish-green bodies with brownish-orange heads and can leave behind mined (i.e., translucent, light brown) needles wrapped lightly in silk (right).

Similar to beech scale, HWA covers itself in waxy coating. The easy way to recognize the adelgid is to look for these white sacs under the branchlets from late fall to early summer. (left). There are numerous native pests that can be mistaken for HWA. Elongated hemlock scale (Fiorinia externa Ferris) is another hemlock pest that feeds on the needles, but it is a native one and so doesn’t create as dire of circumstances as HWA (center). Hemlock needleminer larva (LATIN) have a pale, yellowish-green bodies with brownish-orange heads and can leave behind mined (i.e., translucent, light brown) needles wrapped lightly in silk (right).

|

Treatments

Soil drenches and injection treatments that can be applied by a certified pesticide applicator. Given that the HWA invasion has yet to fully arrive into Leelanau county, it is best to check your hemlocks annually for the white sacs or other signs of stress. If you suspect HWA, send photos to the Invasive Species Network HWA monitoring program linked to the right. Contact an arborist and/or Ellie Johnson, District Forester (231-256-9783 or [email protected]). Works Cited and Extra Resources

|

HWA Surveys by the NW Invasive Species Network (ISN) If your home or land falls within the below parameters, you are encouraged to complete a landowner survey! Homeowner Associations are also welcome to participate. If you have questions, please contact ISN Habitat Management Specialist, Murielle Garbarino:

(231)941-0960 x29 or email [email protected]. Do You Qualify For a Site Visit?

If your home or land falls within the listed parameters, you are encouraged to fill out the below landowner form: |

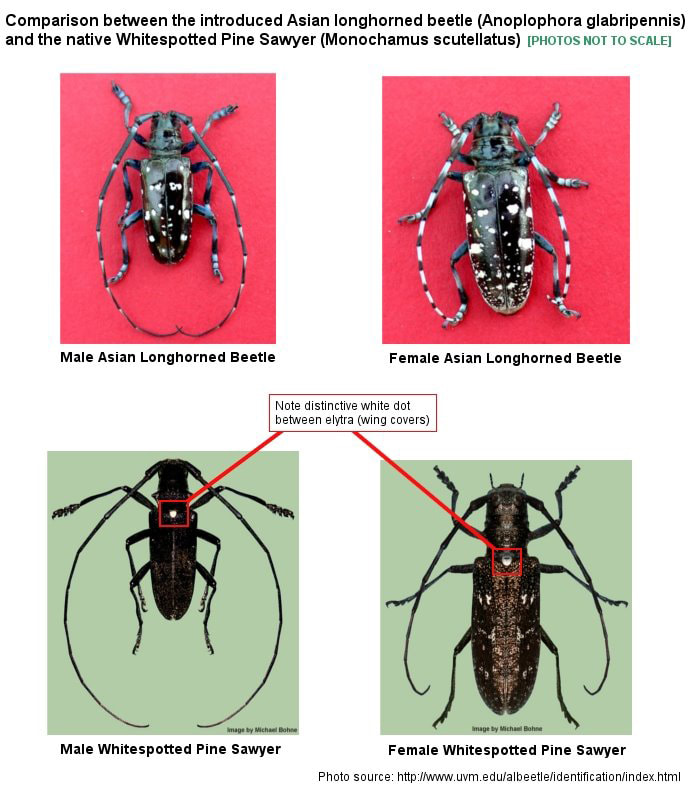

Asian Longhorn Beetle

|

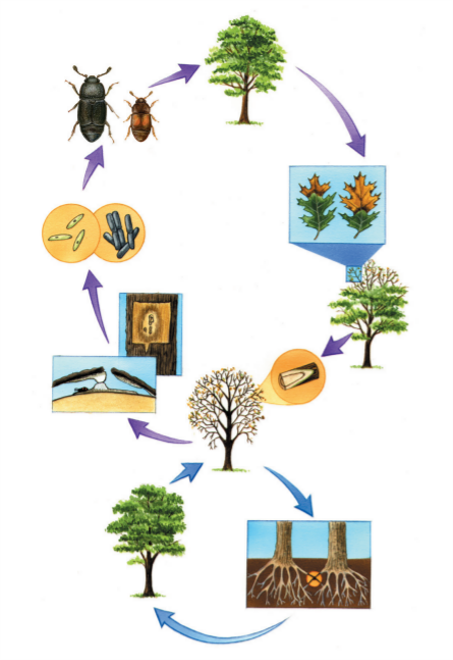

Ecology

Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) is a pest not yet found in the state of Michigan. It is best to be on the lookout as this beetle is capable of killing a plethora of tree species both ornamental and marketable. The full list of trees impacted by the beetle is not yet known. New York State suffered an invasion in the last 15 years where the trees impacted included: Norway maple (Acer plantinoides), sugar maple (A. saccharum), silver maple (A. saccharinum), box elder (A. negundo), sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), birch (Betula spp.), elm (Ulmus spp.), poplars (Populus spp.), and willows (Salix spp.). Beetle larvae bore feeding tunnels through the tree's sapwood and cambium creating many internal wounds and sap leakage that could eventually lead to tree mortality. Infested trees become structurally unstable and can drop branches or break in strong winds, making them increasingly hazardous as the infestation progresses. The lifecycle of the Asian longhorn beetle is most active in the summer. The adults are usually active from May through October with a peak around midsummer. The females will chew oval-shaped holes in the bark and deposit eggs underneath. The eggs only need two weeks to hatch and the larvae begin feasting on the tree immediately. They will stay within the tree feeding over the winter and bore out of the tree from late spring to midsummer as young adults. They will continue to feed on twigs and leaves until reaching breeding maturity. |

August is tree check month. Photo: MSU Extension

August is tree check month. Photo: MSU Extension

Signs and Symptoms

MSU extension recommends the following symptoms to look for in possibly infected trees:

MSU extension recommends the following symptoms to look for in possibly infected trees:

- Look for slightly smaller than dime-sized exit holes. The holes are perfectly round and should be big enough for a pencil to easily be inserted.

- Look for shallow scars in the bark. These scars indicate that the ALB has chewed through the bark to deposit eggs, likely in the same tree from which it hatched.

- Look for sawdust-like material on the ground or on tree branches. This material is produced as the larva bore, or chew through the interior of the tree before emerging.

- Look for branch breakage. The ALB larva may initially only inhabit a portion of an infected tree, cutting off water and nutrients to that portion, or branch, killing it without noticeably affecting the rest of the tree.

Treatments

Treatments are still in development for managing Asian longhorn beetle outbreaks. If you suspect this pest is on your property, please connect with Ellie and contact the NW Invasive Species Network (https://www.habitatmatters.org/our-team.html).

Treatments are still in development for managing Asian longhorn beetle outbreaks. If you suspect this pest is on your property, please connect with Ellie and contact the NW Invasive Species Network (https://www.habitatmatters.org/our-team.html).

Works Cited and Extra Resources

- ALB, Michigan Invasive Species: https://www.michigan.gov/invasives/news/2022/08/09/time-to-check-trees-for-invasive-asian-longhorned-beetleSigns and damage of ALB, Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry: https://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/caps/ALB/ALBdamagepics.shtml

- August is tree check month - MSU Extension

- MSU Extension, Asian Longhorned Beetle: An Exotic Pest That We Don't Want in Michigan (E2693) - MSU Extension

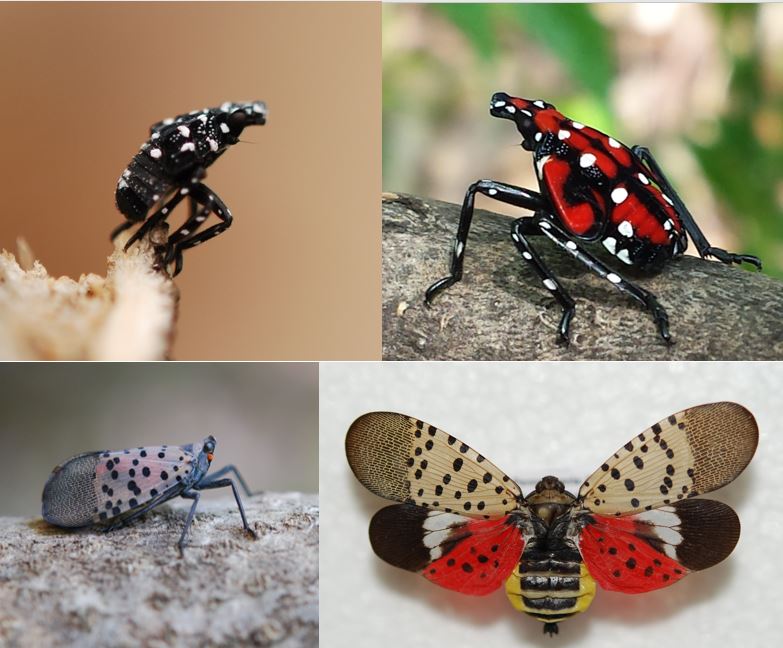

Spotted Lanternfly

Spotted lanternfly: New pest alert for Michigan tree fruit growers. Photo: MSU ext.

Spotted lanternfly: New pest alert for Michigan tree fruit growers. Photo: MSU ext.

Ecology

Spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula), is an invasive plant hopper insect that has potential to cause harm to vineyards and numerous tree species in Michigan. It has been observed to feed on: tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), grapevine (Vitis spp. - wild and cultivated), red maple (Acer rubrum), black walnut (Junglans nigra), butternut (Juglans cinera), birch (Betula spp.), willow (Salix spp.), and sumac (Rhus spp.). In general, a spotted lanternfly infestation is not enough to kill native tree species, but they can if the tree is already under stress. When feeding, the adults will excrete sticky sap-like substance called honeydew that turns into a black mold that will be very noticeable at the base of an infested tree. It does not feed directly on fruit but rather the leaves, buds and sapwood which can cause carbohydrate loss and stress to the plants.

The lifecycle of the spotted lanternfly occurs in four cycles, or “instars”, before reaching maturity. Eggs are laid in late September until adults are eventually killed by freezing temperatures, and then they overwinter until hatching the following spring. In the smaller life stages, they will prey primarily on fruit trees and vines transitioning to bigger woody organisms as it matures. Adults are not great fliers but can successfully make it to an adjacent tree slowly advancing spread. An important note is that spotted lanternfly need tree-of-heaven to develop through instars and to successfully reproduce. They will feed and lay egg masses on numerous tree species (and even lay eggs on things that aren’t trees, like cars, poles, homes, etc.), but they will lay fewer eggs with fewer surviving/developing young if there are no tree-of-heaven in their vicinity.

Spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula), is an invasive plant hopper insect that has potential to cause harm to vineyards and numerous tree species in Michigan. It has been observed to feed on: tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), grapevine (Vitis spp. - wild and cultivated), red maple (Acer rubrum), black walnut (Junglans nigra), butternut (Juglans cinera), birch (Betula spp.), willow (Salix spp.), and sumac (Rhus spp.). In general, a spotted lanternfly infestation is not enough to kill native tree species, but they can if the tree is already under stress. When feeding, the adults will excrete sticky sap-like substance called honeydew that turns into a black mold that will be very noticeable at the base of an infested tree. It does not feed directly on fruit but rather the leaves, buds and sapwood which can cause carbohydrate loss and stress to the plants.

The lifecycle of the spotted lanternfly occurs in four cycles, or “instars”, before reaching maturity. Eggs are laid in late September until adults are eventually killed by freezing temperatures, and then they overwinter until hatching the following spring. In the smaller life stages, they will prey primarily on fruit trees and vines transitioning to bigger woody organisms as it matures. Adults are not great fliers but can successfully make it to an adjacent tree slowly advancing spread. An important note is that spotted lanternfly need tree-of-heaven to develop through instars and to successfully reproduce. They will feed and lay egg masses on numerous tree species (and even lay eggs on things that aren’t trees, like cars, poles, homes, etc.), but they will lay fewer eggs with fewer surviving/developing young if there are no tree-of-heaven in their vicinity.

|

Signs and Symptoms

|

Treatments

A number of pesticides already in use can work on controlling spotted lanternfly infestations. It is best to consult with an arborist, Ellie, and/or the NW Invasive Species Network (https://www.habitatmatters.org/our-team.html) if you have any questions.

A number of pesticides already in use can work on controlling spotted lanternfly infestations. It is best to consult with an arborist, Ellie, and/or the NW Invasive Species Network (https://www.habitatmatters.org/our-team.html) if you have any questions.

Works Cited and Extra Resources:

- Controlling tree-of-heaven and why it matters, Penn State extension: https://extension.psu.edu/controlling-tree-of-heaven-why-it-matters

- First detection in Michigan, MSU extension: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/first-detection-of-spotted-lanternfly-in-michigan

- Good management considerations from PSU extension: Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide (psu.edu)

- MSU extension with general info: Spotted lanternfly: New pest alert for Michigan tree fruit growers - Fruit & Nuts (msu.edu)